How fair is your fashion communication?

An intro to social washing and how to check your comms for ethical pitfalls.

The Crisps is your newsletter for anti-greenwashing and honest fashion communication. But speaking about sustainability in fashion doesn’t just include ecological aspects. It also means social justice, biodiversity loss, animal welfare, and much more. That’s why this week, we’re looking at social washing.

Which colleague or friend should read this issue?

This week marks a tragic anniversary that forever changed the fashion industry: the Rana Plaza collapse. On April 24th, 2013, the eight-story building which hosted several textile production floors collapsed in Dhaka, Bangladesh. More than 1.100 people were killed. More than 2.500 people were injured.1

Since Rana Plaza the discussion around safe working conditions, fair pay and other social aspects of fashion has evolved tremendously. And while there has been progress in some areas, most of them still very much lack behind. Wage exploitation? Still common. Sexual harassment? Still common. 14-hour workdays and unpaid overtime? Still common.2

Even though there’s only little progress on the ground brands use bold statements about producing ethical fashion, paying fair wages, and being diverse. But to achieve progress, social justice, diversity and fair practices can’t just be marketing claims. They have to be incorporated, practiced and (just as it is with green claims) backed up by action and justice. If they are not, brands risk being called out for social washing, blocking a just transition, and legal damages.

Receive The Crisps directly to your inbox every other week – by subscribing for free in just a few seconds.

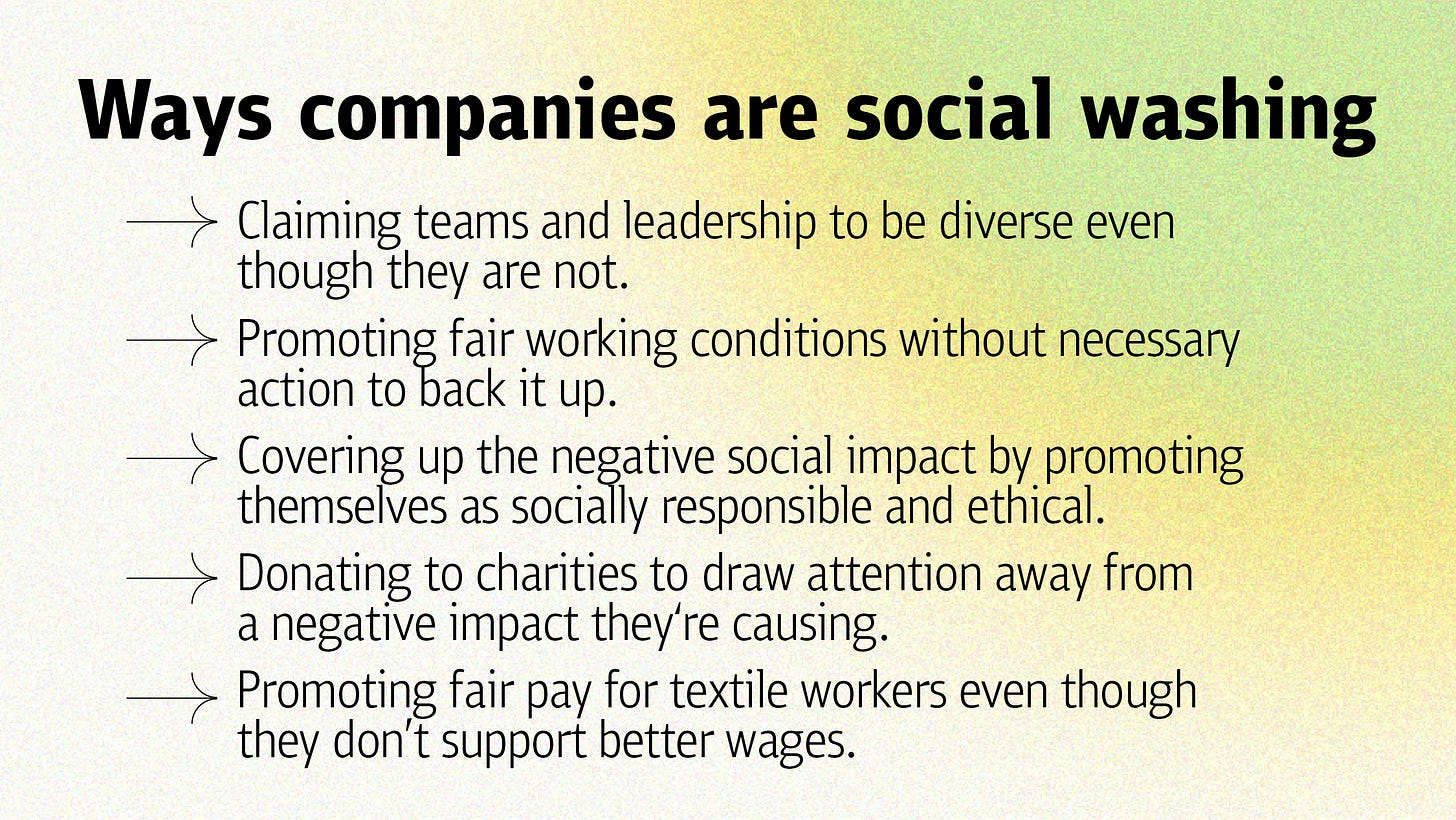

Similar to greenwashing brands use social washing for financial gain, brand reputation, or publicity. Most of the time social washing revolves around human rights, gender diversity, equity, inclusion, working conditions and fair pay.345 Here are a few examples:

Is there any kind of social washing litigation?

If the EU Green Claims Directive is approved, it might also become relevant to vague and unsubstantiated social claims.6 Until now there have not been many lawsuits relating to false or misleading advertising based on supply chain integrity, human rights, and employee benefits. But relating to cold-cutting contracts, employee conditions and remuneration, brands had to pay up.

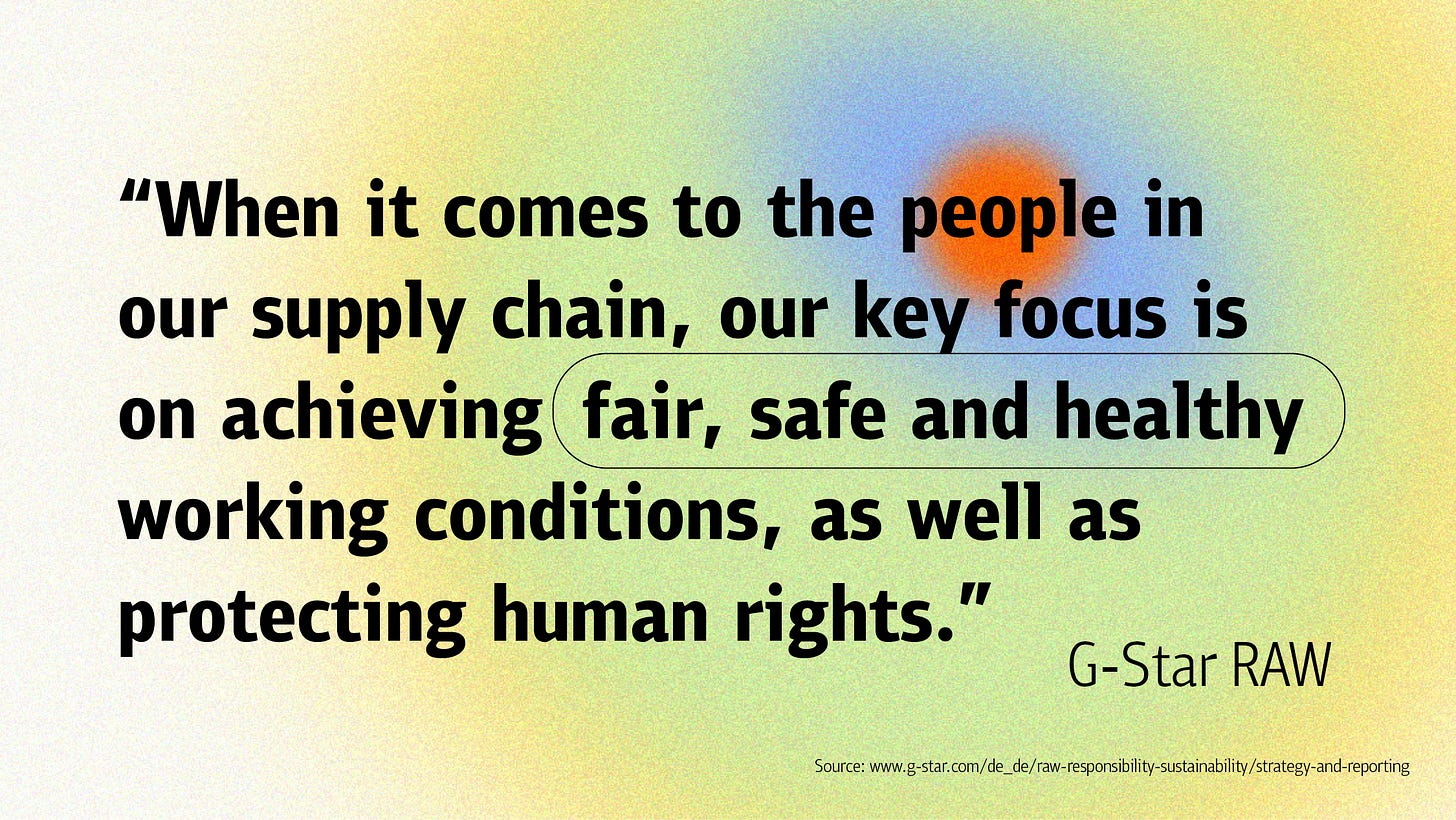

Just recently, the Dutch denim brand G-Star Raw had to pay damages and interest to one of its Vietnamese suppliers. What happened? During the pandemic, G-Star Raw canceled orders for a specific jacket model. Because of the financial damage to the Vietnamese supplier local workers lost their jobs. So the supplier demanded a € 16 million payment claiming the brand did not respect its commercial terms which were linked to its CSR policy and public strategy advocating for fair negotiations. The case went to court and the supplier won. On April, 7th, 2023 the Amsterdam court ruled that G-Star Raw is responsible for the losses and damages of its supplier.7 8

The key motivator for the court’s decision was the dismissal of local workers which was not in line with the CSR policy and publicly made ethical commitment by G-Star Raw. On its website9, the brand states the following:

Takeaway: While there is not yet a whole lot of legislation regulating social claims, the G-Star Raw case sends a strong signal that brands have to pay up if their communication and actions don’t align. Also if it’s focusing on social aspects.

Areas, where legal claims for damages could arise, include:

alleged underpayment or wage theft

company culture issues (bullying and harassment)

supply chain human rights issues

Top 3 myths evolving around social washing:

Transparency is justice. While disclosing data on social working conditions in supply chains might have a positive effect on ethical consumer perception, don’t confuse it with accountability and justice. The fundamental rules have not yet changed, making it still difficult for most workers to achieve justice through sole transparency.

“Made in Europe” is a safe haven. Nope, it is not. Free trade within the European Union is not to be confused with fair trade. Because there is widespread evidence that working conditions in Europe lack due diligence and security for garment workers.

Brands paying fair wages. Most brands do not own the factories where their clothes are made. Instead, they outsource their manufacturing. So it’s the manufacturers paying textile workers wages. Brands pay prices for the products they buy from supply chain partners.

AD

There’s not enough action to bring living wages for garment workers on the way. While we know the process of actually changing the Status Quo is difficult, there’s something each EU citizen can do right now to help make legislation for living wages a reality.

Share the campaign within your organization and network

What to keep in mind to avoid social washing:

🔸 Look for your “Industrial-Colonial-Patriarchal White Savior Complex”: The term was introduced by Marcelo Saavedra-Vargas and points out the small changes Western businesses actually manage which tend to increase the huge divide between the South and the North.10 One common example is “we produce in India because we create jobs in the Global South.” (There will be an entire issue around this topic soon.)

🔸 Properly contextualize: Communication about the people involved in a business is never a sales pitch. It’s about sharing insights with the audience and explaining relations and interconnections. Context builds trust and connection which is why context matters. Stop speaking about “your“ suppliers or “your” cotton farmers. You do not own them.

🔸 Represent respectfully: Garment workers have rarely seen themselves authentically represented in ads and on social media in the past. But proper representation is an essential part of responsible communication. If your company is going to create advertisements that include people from factories, agriculture, or underrepresented groups, don’t tokenize them. Instead include them in the creation of the ad or communication.

🔸 Carefully use fair and ethical: Don’t use terms like fair and ethical if you don’t actively follow the principles–internally as well as in your supply chains. A possible scenario would be: A brand's employment practices, supply chains, or products harm people and the wider society but through social washing the brand is selling more and therefore causing more harm.

🔸 Don’t guarantee safe working conditions: You’ve got voluntary codes on fair working conditions? Even though it is one way for brands to respond and potentially deflect demands, be careful with using “fair working conditions” in your comms. Because voluntary codes rarely bring meaningful improvement.

🔸 Don’t disclose selectively: Every time brands talk about improvements but leave out contradicting or inconvenient information, it’s a case of selective disclosure. That would be the case if a brand talks about better incomes for cotton farmers, while the cotton farmer is bound to global market prices.

Want to know more about social washing? Make sure to receive our pro version next week. In the meantime, you will find further readings and resources below.

Have a great weekend,

Tanita & Lavinia

Don’t miss the last days of our launch discount. Save 30% off your first year by subscribing to the pro version of The Crisps.

Further information on social washing:

Guideline on respectful fashion activist communication by Lavinia Muth (2023)

Foster, D. J. (2018). Selling Whiteness?—A Critical Review of the Literature on Marketing and Racism. Journal of Marketing Management, 34(1/2), 134-77.

Vredenburg, J., Kapitan, S., Spry, A., & Kemper, J. (2018). Woke washing: What happens when marketing communications don't match corporate practice. The conversation.

Slowfactory (2023): Reparative Media with Dr. Aymar Jéan "AJ" Christian. Video:

(accessed 21.04.2023)

Barua, U., & Ansary, M. A. (2017). Workplace safety in Bangladesh ready-made garment sector: 3 years after the Rana Plaza collapse. International Journal of Occupational Safety and Ergonomics, 23(4), 578-583.

Antonini, C., Beck, C., & Larrinaga, C. (2020). Subpolitics and sustainability reporting boundaries. The case of working conditions in global supply chains. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 33(7), 1535-1567.

Goldman, N. C., & Zhang, Y. (2022). Social Washing or Credible Communication? An Analysis of Corporate Disclosures of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in 10-K Filings. An Analysis of Corporate Disclosures of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in.

Baker, A., Larcker, D. F., McClure, C., Saraph, D., & Watts, E. M. (2022). Diversity Washing. Chicago Booth Research Paper, (22-18).

Griffin, N. (2022). A risk based perspective on greenwashing and social washing. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/risk-based-perspective-greenwashing-social-washing-naomi-griffin/?trk=articles_directory, (accessed 17.04.2023)

European Commission, Directorate-General for Environment, (2023) Proposal for a Directive on green claims. https://environment.ec.europa.eu/publications/proposal-directive-green-claims_en, (accessed 22.03.2023).

Rechtspraak (2023) ECLI:NL:RBAMS:2023:1913. https://uitspraken.rechtspraak.nl/#!/details?id=ECLI:NL:RBAMS:2023:1913&showbutton=true&keyword=g-star&idx=4, (accessed 17.04.2023)

Fashion Network (2023) G-Star Raw ordered to pay damages to Vietnamese supplier. https://ww.fashionnetwork.com/news/G-star-raw-ordered-to-pay-damages-to-vietnamese-supplier,1506161.html (accessed 17.04.2023)

G-Star Raw Corporate Website EN, Raw Responsibility. Strategy and Reporting. https://www.g-star.com/de_de/raw-responsibility-sustainability/strategy-and-reporting, (accessed 17.04.2023)

Diverse authors (2022). White Saviorism in international development. Theories, practices and lived experiences. Indigenous Cultures and the Industrial-Colonial-Patriarchal White Savior Complex by Marcelo Saavedra-Vargas, 27-41.